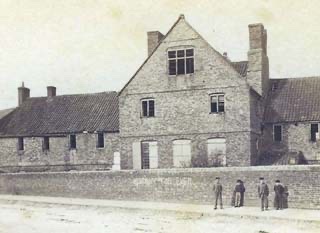

THE WORKHOUSE

In Black Hearts And Blue Devils there is a Workhouse, which I have set in Tippity Green, a part of Rowley. In fact, there was a workhouse in Rowley in former times. It was once part of the Dudley Union which included establishments at Tipton (mentioned in the book), Sedgley and of course Dudley. The Rowley workhouse had 60 inmates in 1777, but could be expected to have grown larger by the time of our story, in the 1880s. That’s the basis upon which the fictional workhouse is written up; with an entirely fictional “master” in the form of Mr Gideon Gross, who is one of the less endearing of the “black hearts” in our tale…

Mention of “The Workhouse” inevitably conjures up images of Dickensian, Victorian institutions. However, the first mention in England of “workhouse” can be traced back to the 1600s. The alternative name of “Poorhouse” is probably more relevant to the latter half of the nineteenth century by which time most inmates were from the ranks of the old, infirm and orphaned or were unmarried mothers. Parish poor relief can be traced back to the end of the reign of Elizabeth I when in 1601 was passed “An Act For The Relief Of The Poor”. It imposed a local property tax (these days expanded in scope and known as council tax) to fund relief of the poor. It made no mention of workhouses but did propose the erection of housing for the impotent poor, i.e. the elderly, incapacitated and long-term sick. However, most relief consisted of “out relief” which took the form of money, clothes and food for the poor in their own homes. The able-bodied poor were viewed differently. The Act envisaged providing out of work able-bodied men with materials to earn money. Those failing to take up the any such offer were liable to imprisonment….

As time passed, parishes looked to save money, or at least use it more efficiently (plus ca change!) and so the “workhouse” proper began to evolve. To ensure that unemployed able-bodied men contributed to society they were made to work in exchange for board and lodging in the workhouse (this was called “indoor relief”). The Workhouse Act of 1773 gave parishes the right to deny “out relief”, paving the way for the larger institutions so graphically described by Mr Dickens. Impetus was lent to this process by the 1830 Poor Law Amendment Act. The general thrust of this Act was to deter reliance on the parish and get people contributing to the economy. To this end, conditions were made as uncongenial as the morality of the day would allow. Coupled with this, all “out-relief” for the able-bodied was ended and any man entering the workhouse was legally obliged to take his family with him: he would have to be desperate indeed. This precipitated the building of very large establishments housing hundreds of a “general mixed workforce”.

By the later half of the nineteenth century (when our story is set) most inmates were, as mentioned above, old, infirm, orphaned or unmarried mothers. From an 1861 survey of Dudley workhouse residents, some of the reasons for their occupancy can be gleaned. It lists: defective vision, injured spine, weak minded and old age, idiot (several times!), injuries received in coal mines, deformity, rheumatism, old age, infirmity, asthma, dropsy, hysteria…

It is against such a backdrop that our Mr Gideon Gross weaves his nefarious web of deceit. How does that work out for him? Read the book to find out!

Post Views : 310