Shrewsbury Gaol In Black Hearts And Blue Devils, Capital Punishment, And The Dudley Throttler.

The plot of the 'Black Hearts' story at a few points briefly takes us outside of the Black Country setting which hosts most of the action. One of the little excursions beyond the Black Country finds us in Shrewsbury Gaol, in 1887. This scene sees the Lively's uncle, Cyril Crane, visiting a condemned man in prison. Condemned to death that is. Without wishing to give too much away, Cyril is there to cut a not altogether above-board deal with one William Arrowsmith (who previously, in the novel, operated under the alias of Alan Hale). I picked the name Arrowsmith because there really was a William Arrowsmith incarcerated there at the time that the novel is set: he was executed on Wednesday the 28th of March 1888 for the murder of his 80-year-old uncle, George Pikerill, whom he had battered to death for financial gain (arguing over a bag of money) on the 11th of November 1887. A James Berry was the hangman.

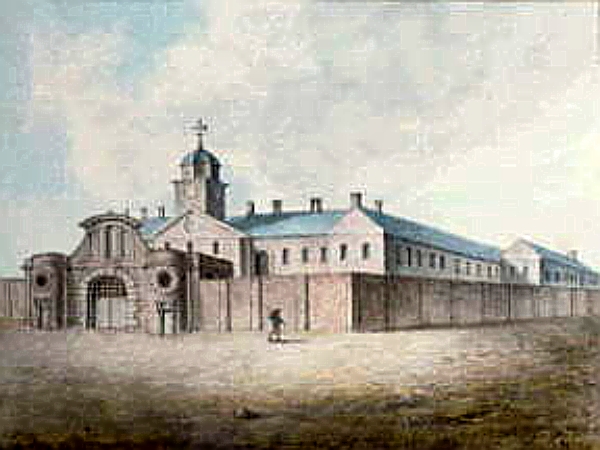

At the time of our tale the gaol building was only ten years' old, having replaced the previous establishment in 1877. Like Smethwick's Galton Bridge, which has an important part later in the story, it was designed by Thomas Telford. From the seventeenth century onwards, criminals were hanged (including a few women), often publicly, at Shrewsbury, for what modern sensibilities would deem very trivial offences, like stealing livestock. Indeed, the first recorded legally sanctioned hanging at Shrewsbury was of 25-year-old John Smith - for stealing ten cotton handkerchiefs at Whitchurch. The biggest single event was when five men were hanged together outside the prison walls in 1811, for a farm burglary.

Criminals from Black Hearts' 'neck of the woods' would have had their necks stretched at Shrewsbury (Stafford gaol also included certain parts in its 'catchment area'!). For example, one Thomas Jesson was executed on the 27th of March 1815 for the murder of his step daughter, Mary Birch, in the parish of Halesowen, by picking the little girl up by the legs and smashing her head against the floor.

Another local connection: George Smith also plied his trade at Shrewsbury -

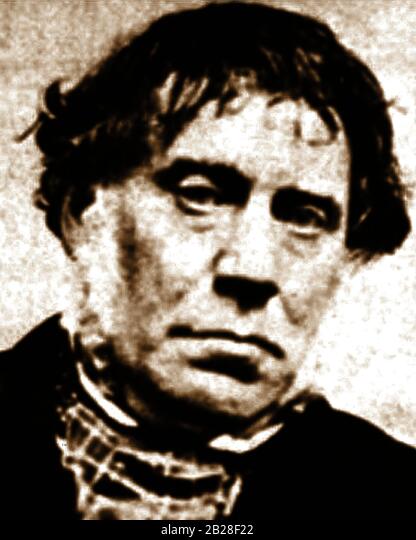

Smith (pictured) was known as the "Dudley Throttler or Higgler", higgler being Black Country slang for a hangman. He was renowned for his long white coat and top hat which he wore at public hangings. He was also noted for being particularly fond of “Black Billy” rum. This may have been the cause of “dropsy” from which he suffered in later years. George Smith got into the hanging business when in 1840, whilst serving a prison sentence at Stafford Gaol for debt, the executioner, William Calcraft, went there to conduct the double hanging of James Owen and George Thomas (11th of April 1840) for the "Bloody Steps Murder" of Christina Collins at Brindley Bank near Rugeley. As it was a double execution Calcraft wanted an assistant but none of the 'Turnkeys', would volunteer, so the governor asked the prisoners if any of them would, on the promise of early release. Smith volunteered and was deemed successful by the governor, with Owen and Thomas seeming to die almost instantly. This led to Smith's appointment for the hanging of 26-year-old Charles Higginson at Stafford on the 26th of August 1843, his first execution as principal.

Although not one of England’s best-known hangmen he assisted William Calcraft at six executions and officiated as principal at 33 public hangings and one private one between 1840 and 1872. Interestingly, George Smith was actually born in Rowley Regis (home to those 'Blue Devils'), where much of the action in Black Hearts takes place. Approximately 30,000 people were at Stafford prison on 14 June 1856 to see the public execution by hanging, at the hands of Smith, of William Palmer, the 'Rugeley Poisoner'. Pieces of the rope which despatched Palmer are said to have sold at five shillings per inch (an alternative explanation for the phrase 'money for old rope', although in the vase of a professional executioner the 'old' would be a misnomer). Five shillings an inch might be an exaggeration but bits of hanging rope were much in demand generally: gamblers were particularly intrigued by the hangman’s rope and thought of it as lucky. One nineteenth century magazine noted that the rope was “a coveted charm of professional gamblers, who suppose it an infallible talisman for securing good luck; probably for the reason that a symbol of especially ill fortune is credited with opposite influences." Pieces of a hangman’s rope was also said to offer more than just luck to gamblers. Fashionable women found them appealing and they even briefly became part of English folk medicine.

We don't know how lucky we are!

Post Views : 428